Image courtesy of the artist

When I was a child, I had an innate curiosity for simply observing things: the shapes of objects on a window sill; light shining through a window making patterns on a carpet or illuminating the corner of a wall; the subtle shades of shifting color in everything around me. These ordinary daily experiences captured my attention. Drawing and painting what I saw was a way to express the beauty and mysterious quality of it all. I also loved the ability to make a gesture with charcoal or paints just for the sheer joy of doing so.

With this fondness for observing and making marks, the word “art” evokes in me a specific way or process of communication by expressing my experience of the moment. More basically, art can be seen through gestures on a surface with graphite and colors, whether they are realistic or abstract. In that way, as a painter, art is fundamentally the process of observation and communication. Training in the disciplines of painting, anatomical drawing, iconography, design, color theory, and so on. have been essential aspects of the development of my visual literacy.

In terms of becoming a professional, one of my Buddhist meditation teachers defined a professional as a person who is ardently dedicated to their chosen discipline through consistent training, humility, and mindfulness in one’s actions.

My mother encouraged me to draw and paint as a child. When I was six she gave me an oil painting kit with pigments, mediums, brushes, and a few canvas boards. I loved the materials; the different types of brushes, the effects I could draw from them, and the alchemy of mixing pigments. With her classic and well-endowed European cultural training and education, she encouraged artistic endeavors in our home such as painting and writing poetry. It was not unusual to spend the evening going through National Geographic magazines to draw from the illustrations and photographs.

I was inspired by the details in the paintings and drawings of past artists: their use of pencil, charcoal, and dry pigment sticks, the way in which they used their brushes, the play of form and space within the illusion of two dimensions, and how all of this was handled with amazing results. Of course, as a child I did not yet have the visual vocabulary that I have now to describe what held my interest in recalling these moments. My experience was direct and nameless. The art I was drawn to captured this beauty and mystery.

As a teenager, I became very interested in the brush paintings and calligraphy of Japanese and Chinese artists. I was intrigued by the power and beauty of single stroke gestures made with brush and ink. Calligraphic gestures were both stunning in their simplicity and powerfully energetic. They presented a play of dimension and space without using vanishing points, but rather through painting scenes in rhythmic receding horizon lines within the continuity presented in scrolled horizontal formats. This seemed to be quite a refined and somewhat enchanting way to convey the landscape’s story.

Image courtesy of the artist

I have primarily gravitated toward two-dimensional artwork because of its compositional capacity to play with the experience of illusion. There is no limit to what can be expressed on a flat surface to bring forth responses within us that are multi-dimensional. This underscored the mysterious qualities of life that I sensed through observing art as a child. When I decided to major in visual arts for my university studies, I wasn’t planning on becoming a professional so much as further continuing my drawing and painting and training in various techniques. My choice in 1966 to enter university as a Visual Art BA student was directed at receiving more specific training with teachers who were painters and designers.

I have a deep respect and personal interest in earnest, diligent training. This education requires effort spawned from an appreciation of master artists in their respective disciplines. It also illuminates a joy for learning and a longing and tasteful sensitivity for discovery. The anatomical studies and sketches of Leonardo da Vinci have influenced me significantly. The paintings of the Impressionists, Joseph Albers’ color studies, Paul Klee’s precision and whimsy, and Van Gogh’s brushstrokes all had a big impact on my work when I entered art school at the college level. Also important were the two American commercial artists Norman Rockwell, with his flawless ability to convey human emotion in utterly familiar ordinary experiences, and the early animations of Walt Disney and his colleagues, their quick-sketch renderings being artistically and technically savvy. I thought each artist—within their own creative expression—showed a broad interest in the complexities of the human situation. I had quite a range of influences!

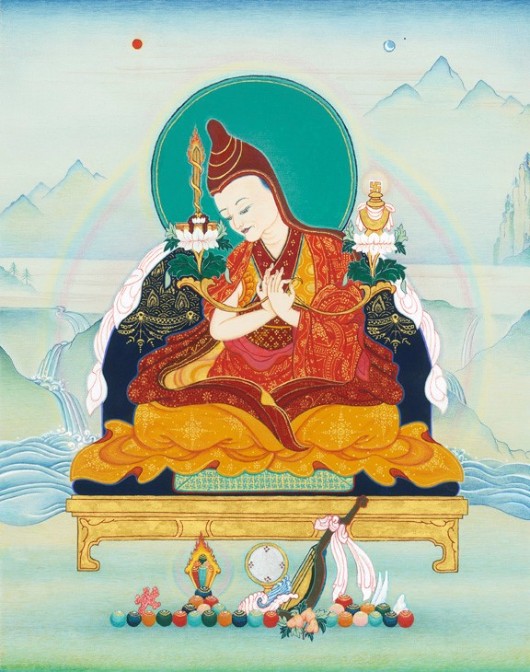

Then, in the late 1960s, I began formal training in meditation in the early Buddhist tradition. Soon after, I became involved in learning about the iconography and painting techniques of Himalayan Buddhist art. At this time, the symbolic meaning of thangka paintings—scroll paintings of Buddhist iconography—remained unknown, with few translated sources of reference. I began to look more discerningly at thangka with a painter’s eye. Their compositions showed influences from various cultures of the Indian, Middle Eastern, and Asian continents; their color palettes reflected the mineral pigments available in the various artists’ environments. And most importantly, I studied the proper proportions (tigse) of hand gestures, postures, and facial expressions.

Private collection, Colorado, USA. Image courtesy of the artist

As I continued training in Buddhist meditation practices with master teachers such as Kalu Rinpoche, Jamgon Kongtrul Rinpoche, Dzigar Kongtrul Rinpoche, and others, the ability of artists from past centuries to convey the heart essence of a buddha’s countenance became more apparent to me. Through studying the Dharma and practicing meditation, my visual discernment was becoming informed in a new way. I was developing a deeper understanding of the symbolism these works of art are meant to convey. I had less interest in the majority of thangka paintings that did not hold such a caliber of excellence. There are master painters of the 18th and 19th centuries, whose names are not known to us, to whom I was particularly drawn. These painters of the eastern Tibetan style were highly influenced by the atmospheric and refined painting techniques of Tang dynasty China. This became the particular style of Himalayan Buddhist iconography that I would be trained in, known as Kharma Ghadri.

Later, in the mid-1990s, when I was invited to teach at Naropa University in Boulder, Colorado—then the Naropa Institute—I began training in the art of Japanese brushstroke practice. Kobun Chino Roshi and Eiichi Okamoto Sensei both guided my training, particularly showing me the essence of brushstroke practice as a spacious present awareness that one attempts to rest in while engaging the brush-ink and paper. A Zen master, Kobun Chino Otagawa Roshi was showing me that such a view and practice is consistent with lucid and dedicated allegiance to Prajnaparamita, the mother of all buddhas and the personification of dependent origination. Meanwhile, Eiichi Sensei’s example came through, testing me by partnering in silent brush stroke exchanges on large sheets of paper rolled across the studio floor. His teaching style steadfastly mirrored the presence of mind necessary in making a genuine mark. Both senseis provided an unshakeable foundation for my progress in exploring the union of creative process and natural awareness, accessible to aesthetic interpretation.

My root Buddhist teacher, Kyabje Kalu Rinpoche, directed me to train in a specific aesthetic path. In doing so, he gave me two vital instructions: “Always stay true to tigse and always dedicate the merit.” Tigse is a Tibetan word meaning proportion, referring to the graph defining the classic proportions of a Buddha figure. More comprehensively, it points to the harmonic relation between the parts and the whole. In its deepest meaning it correlates with the alignment of body, speech, and mind, which is also discovered through the direct meditation experience. This alignment has permeated my traditional and contemporary artworks. In this drawing of Rinpoche’s portrait from various angles, the tigses are barely showing. This study marked the beginning of my interest in the combination of Western portraiture and traditional Buddhist iconography and symbolism.

gold on silk. Private collection, Colorado, USA. Image courtesy of the artist

A few other portraits of meditation masters followed this drawing. I became thoroughly engaged in remaining true to the correct proportions of a buddha figure (tigse) while rendering each personal portrait in their own familiar likeness. Intentionally, I drew the countenance and gaze of each person to speak directly to our humanness and deep-rooted responsive connection that marks sentient existence. Thus, the Buddha tigse became a discerning structure, through which I could convey an intimate clarifying equilibrium inherent to the human figure’s ability to express qualities of receptivity, warmth, and wakefulness: this is sila, the ethical qualities of an enlightened heart or mind.

Another example of how Buddhist themes appeared in my artworks came in sequences of large brush-ink art, shown in my Six Bells paintings. This sequence came forth while I was studying and contemplating the final day and night of the Buddha’s coming into complete awakening. There are many stories of this final stage of his evolutionary path toward sustained peace, complete knowledge, and resultant liberating activity. This painting shows the fourth part of the day, named Evening Watch. It is the transition from day into night, when many alluring distractions can provoke concentration and deceive insight. The Buddha sits nearly transparent at the base of a tree. At his hara—the central energy area at the lower belly—a black Buddha brushstroke sways blithely to the vivid colors of illusory arising. All the Buddha brushstrokes throughout the composition: large, small, right-side-up, and up-side-down, are true to tigse. This adherence to traditional proportions was my way of indicating that whatever the outer form, allegiance to time-honored design structures can hold the authentic truth of symbolic visual dharma.

The Dalai Lama gave me great encouragement and a humble example when he consecrated the Chagdrukpa thangka (Six-armed Mahakala). It has been a permanent piece in the Denver Art Museum’s (DAM) collection of Buddhist art since 1995. The education director of the museum told me that it was the first traditional Vajrayana scroll painting to become part of a major American museum’s permanent collection that states, “Country of Origin: The United States of America.” This acquisition was supported by a patron of the visual arts whose family collection includes influential 20th century American artists. The paintings they have acquired have proven over time to be original and astute, thus influencing the development of modern art.

My artist residency at DAM involved several public visual lectures, including to patron groups such as the Asian Art Association of the Denver Art Museum. Their Asian Art Collection spans a substantial period, beginning with the fourth millennium BCE to the present. It displays artworks representing a diversity of achievements by artists and artisans of Eastern-based iconographies. Along with the visual teaching lectures, for several months I worked on the painting at the museum three to four hours, three days per week, with one of those days being while the museum remained closed to public visits. On those days I spoke with museum custodians, chaperones, gallery directors, and installation designers, who would come in randomly to sit for a while, observing, asking questions, and engaging in light conversation with me. Denver newspapers and other local papers wrote articles and published interviews. Local audio and visual news recorded the Dalai Lama consecrating the thangka on his first visit to Denver and the surrounding Front Range area of the Rocky Mountains. This was the second of my paintings that His Holiness had blessed, the first being in a private meeting during his first visit to San Francisco and the surrounding Bay Area in 1980. At DAM, the prominent gallery dedicated to this unique direct-experience exhibit was beautifully and spaciously arranged, a part of the museum’s floor dedicated to Asian Art. The walls displayed the preliminary drawings and brush-line ink drawings for all six figures that I painted in the final thangka. On a low spacious platform in the center of the gallery, I painted while 5–7 visitors could sit in chairs and silently watch the progress. People could also walk around the room and sit on benches to view the preliminary drawings. This opportunity combined art exhibit with education event, and offered an intimate opportunity to observe and dialogue with an artist at work. I loved the arrangement and, surprisingly, the exposed experience of such a public temporary studio!

In 1988, I was invited as a guest artist of thangka painting to the summer session of Naropa University. Beginning in the fall of 1990 and the subsequent four years, I designed and implemented the institute’s first BA degree in the visual arts. Launched in the fall semester of 1994 and serving as chair of the department for its seminal first four years, as a core faculty member I was put on the spot to express “bone knowledge,” the truth and integrity of my experience in the moment. Non-traditional artwork began to emerge in my studio, which instinctively was informed by my traditional training in both Eastern and Western techniques. As chair of the visual arts, encouraging collaboration between the faculty members that I hired specifically for the degree program, I also became a brushstroke student to Kobun Chino Otagawa Roshi and Eichi Okamoto Sensei. These two master artists led me into the refined warrior world of Japanese calligraphy and spontaneous brushstroke.

Both senseis trained me in a spacious, open-minded approach to brush practice, by facing the white space of the paper with little conceptualization to interfere with the movement of the brush. This skillful method coincided with consistent practice of the basic strokes of Japanese calligraphy, or shodo, and copying the short form of the Heart Sutra repeatedly. At this time, I also became intimately familiar with the maitri and mandala and mudra space awareness practices introduced in the early years of the Institute by its founder, Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche, and in the case of these unique maitri practices, with Shunryu Suzuki Roshi.

In the series that came to be known as Sky Dancers: An Exploration in Precision and Grace, I wrote in my art journal and painted in the studio through expressive large spontaneous brushstrokes of wisdom dakinis, or wisdom sky dancers. I kept the brushstrokes that were true to tigse, measuring their accuracy after they dried. I was curious to see if the precision and grace of the specific proportions of a buddha figure had really seeped into my artistic anatomy, a kind of “bone knowledge” test. These spontaneous brushstrokes seemed like a viable kinetic experiment to prove or disprove that inquiry. In other sequences of painting I played with the magnetism and command of mudra gestures (Turning the Wheel: A Travel Game), the abundant display of mandala environment (Golden Ground Series), and the pristine seeds of maitri practice (Maitri Seed Series). I sketched and wrote in my journals. For non-Buddhist audiences, I used visual presentations in singular and provocative ways to accentuate lectures on the liberating symbolism inherent to Buddhist art.

mineral pigments, gold on silk. Private collection, the Netherlands.

Image courtesy of the artist

Indelible Presence (IP) is a set of primary creative practices I have developed over two decades using brush, ink, and paper—the three sacred elements of Asian calligraphy. These three elements provide us with a flawless lens through which we can explore the possibilities of a seamless attentiveness and innocence coursing through our lives. Each May, I lead IP sessions within silent meditation retreats. In the late 1980s in Boulder Colorado, while I designed and eventually initiated Naropa University’s first bachelor of arts degree program in the visual arts, I began to explore the more inneraspectof tigse in a variety of ways, both with the controlled precision of fine, nearly single-haired brushes of thangka painting and also with the dynamic immediacy of large Japanese calligraphy brushes. Beginning in 2001, the practices I had done primarily in the privacy of my studios took on new dimensions. I began leading IP retreat practices within various university programs designed toward a contemplative education experience. Following that, I taught IP practices regularly over six years to a group of education research professors in the Netherlands.

These brushstroke performance exercises named “Indelible Presence Brush Practice” came forth quite readily, with fresh variations continuing to this day. They provide an expressive counterpart to the introspection of retreat by mirroring the basic stages of mindfulness meditation practice. Arising out of the outdoor—preferably wilderness—environments we practice in, and the studio arrangements that I create ahead of our sessions designed to support the basic brushstroke practice we do each day, each retreat with its unique community of participants results in organic and uniquely fresh art performances. By performance, I mean a singular or group activity done to consciously arouse mindfulness, presence, and wonderment, in this case through art.

Making time for meditation retreats has often been an annual part of my life, inspiring and guiding my artistic career. And as I have touched upon already, I feel that visual “art” expresses the unspoken word. My first retreat occurred in 1970—a two-week anapana/vipashyana retreat, based in the practices of the Theravada tradition. It was a very significant experience for me—establishing firmly my return to retreat again and again—to meditate in supportive environments with discipline and guidance.

In between retreats was the time for studying the philosophy and epistemology presented in the Buddhist sutras and tantras through their respective commentaries. Meditation in the Buddhist tradition is a training of the mind with the co-existing development of heart-felt compassion. Through this path of wakeful and ethical intention, wisdom develops into the realization of the true nature. The visual discovery process I felt drawn to was now laced with techniques to explore the inner aspects of my mind and experiences—techniques used for centuries and with proven results. My “time in the studio” provides an analogous opportunity, whether the creative process is occurring indoors or outdoors. I refer to this as my studio environment and studio embodiment time. Making art holds all the discovery opportunities, just as meditation retreat time does. For me, they are strong complimentary to one another.

Writing from my personal experience, the insights and effects of meditation can be expressed through creating visual works of art. Likewise, creating works of art can support one’s meditative journey profoundly. Performance art is an active expression of this natural creativity. This can happen in my studio environment alone, or through outdoor group dynamic situations, such as “One Continuous Gesture.” Art has the power to access a different part of all of us. This part transcends race, color, creed, gender, political persuasion, and national boundaries. This is good news. This kind of news is appropriate right now. Art can bring us together, honoring diversity, pointing to challenges and changes needed, and underscoring our amazing humanity that fortunately remains defined within the natural cycle of all beings’ evolution. And art can bring truth and joy into our lives. Let’s capture the moment, be present for one another, and develop kindness and clarity in our intentions and actions. The Buddha did.

Art and the spiritual are linked together in how I view the world, which I consider the portal of a true spiritual life. My spiritual life is the path of creating works of art intertwined with the path of meditation methods that keep me connected to this reality. The wisdom of the Buddha’s attainment and the subsequent meditation forms he taught underscore this buoyant and prodigious association. Spiritual life is a living system developing as we age, akin to physical development yet capable of nurturing an enduring joy and vitality at any age. Now in the later part of my creative life, I wish to delve more deeply into the contemporary aspect of my painting and performance career.

This article has taken me from childhood through adulthood and, with this question, to the present direction of my career as a visual artist and educator. The influence of the teaching and meditation guidance stemming from Shakyamuni Buddha’s enlightenment, is my muse both experientially and symbolically.

I would like to conclude by saying a little about the art that is beginning to appear now in my studio. As I mentioned, I am poised to delve more deeply into the contemporary aspects of my painting, performance, and contemplative education career. One result of this intention is of a nurturing collaboration forming with an ecology and environmental institute on the Hawaiian Islands. Creating and installing artwork commissioned specifically for the land, its grounds and buildings, while analogous to the actual artwork, designing and introducing contemplative education practices that will compliment the Institute’s core values. Having art and contemplative education practices support the place-based experiential learning programs the physical land offers, now and into the future, has captured my attention fully. I am very inspired by this collaboration. It actively cares for the health of our future and generations to come, through honoring both the enduring discoveries of age-proven indigenous wisdom and present-day scientific knowledge that we witness daily.

Interestingly, the artwork I have begun to design is also touching into my own ethnic Dutch-Hawaiian heritage. Art carrying such a global unifying message is palpable. Capable of reflecting a tangible certainty that touches us uniquely because it has the potential to “reach into our minds” and touch our enduring hearts. So, I will close now and turn attention once again to the drawing board with this appealing and challenging project before me.

Cynthia Moku is an accomplished artist in Japanese brushwork and Buddhist scroll painting. A student of Kyabje Kalu Rinpoche, among others, Cynthia is the founder of Naropa University’s Visual Art Degree Program. Learn more about Cynthia Moku and her artwork at cynthiamoku.com.