From tibet.net

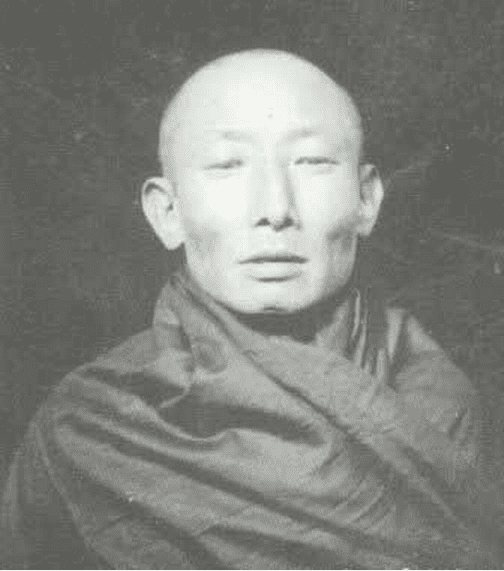

The ongoing coronavirus quarantine and social-distancing conditions that so many of us around the world are facing now do offer a silver lining of sorts, as they allow one an opportunity to return to long-forgotten, albeit eclectic, writing themes. For me, this includes the somewhat infamous character of the celebrated Tibetan intellectual Gendun Chophel, renowned in Buddhist and Tibetan circles as a writers’ writer.

Chophel was such an important and prolific poet, scholar, travel writer, and artist—clearly a man ahead of his time—that it is almost impossible to go to any Tibetan conference without his name being mentioned. I was recently at a forum in Sarnath, India, and heard his name tossed about by a student, ringing a bell deep within my consciousness.

I have written about Chophel before, in my first book of essays, in an account of a trip I took to the erstwhile home of Russian artist and scholar George Roerich, high in the Indian Himalaya in a town called Naggar, just outside the tourist hotspot of Manali. Chophel stayed there for two years, during which he worked on the translation of a 15th-century historical document.

I even reference Chophel on a few occasions in my recent novel, in which I cite the famous poem he penned during his 12-year sojourn in India and Sri Lanka. Here is the poem in full:

My feet are wandering ’neath the alien stars.

My native land—the road is far and long.

Yet the same light of Venus and Mars

Falls on the small green valley of Repkong

Repkong—I left these and my heart,

My boyhood’s dusty plays—in far Tibet.

Karma—that restless stallion made of wind,

In tossing me where will it land me yet?

I’ve drunk of holy Ganga’s glistening waves

I’ve sat beneath the sacred Bodhi tree,

Whose leaves the wanderer’s weary spirit lave.

Those sacred land of Ind—I honor thee,

But, oh that little valley of Repkong.

The sylvan brook which flows that vale along.

Born to a Nyingma family and recognized as a reincarnate early in his life, it did not take long for people to recognize Chophel’s brilliance, and he quickly established himself as a raconteur and an enfant terrible. He was already designing mechanical toys in his youth and was known to be taking English lessons from a Christian missionary. Chophel would later study at Labrang Monastery in present-day Gansu Province, before moving to study for a Geshe Lharampa (doctorate) at Drepung Monastery near Lhasa. Besides his work as a scholar, he was also making a living as an artist at the time. One of the turning points in Chophel’s colorful life was his meeting in 1934 with an Indian scholar and Communist Party member named Rahul Sankrityayan, with whom he worked collecting lost Sanskrit texts in Tibet. Sankrityayan subsequently brought Chophel to India. Their legacy is felt to this day as many of these texts currently lie in Bihar Museum awaiting translation.

Chophel’s years in South Asia helped him fully live up to the promise he had shown as a child prodigy. He wrote many books on Buddhist philosophy, translations from Sanskrit to Tibetan, including a guide to the sacred sites of India, and a Tibetan answer to the Kamasutra, while also working on several dictionaries and numerous poems. He translated, among other works, Kalidasa’s play Shakuntala, the Ramayana, and parts of the Bhagavad Gita. Much of his academic work was so specialized—for instance, the Adjournment for Nagarjuna’s Thought, which he wrote in India—that it would not make much sense even to the informed reader. Lay readers, however, were introduced to Chophel’s thinking through his journalism, in which he debunked popular theories in Buddhism. He published them in such avenues as Maha-Bodhi, the Journal of the Mahabodhi Society of India, and The Mirror, a Tibetan-language newspaper published in Kalimpong.

His life in India coincided with an era of great change. India would soon become independent and the British were uneasy with Chophel’s presence there. They had kept a file on him (unsurprisingly) and had even written to the authorities in Lhasa about Chophel’s scholarly activities.

One of the greatest mistakes Chophel ever made (as many latter-day observers would come to believe) was in returning to his homeland. Some nostalgia notwithstanding, it seemed that Chophel was not particularly looking to return to Tibet.

His admirers were planning to ferry Chophel off to the US. It was the time of the Second World War and Chophel’s hopes to raise awareness about Tibet in North America failed to materialize after his visa application to the US was rejected. His sponsors had even procured land in California, which was dubbed “Tibetland.” Chophel was left with no choice but to return to Lhasa in 1945. He was jailed a year later for two years on trumped-up charges by the Lhasa government (some more naïve Tibetans even entertain the notion that had he managed to reach America, Chophel could have possibly saved Tibet from being swallowed by Mao’s army).

In 1951, Chophel saw from his rooftop the People’s Liberation Army march into the Tibetan capital Lhasa. He was seriously ill, probably due to cirrhosis of the liver (he was a heavy drinker and a smoker). Tibet’s first modern-day (and post-colonial scholars) would meet a sad end (in his writings Chophel made no secret of his disdain for Western colonialism). He was born when the British invaded Tibet and died when the Chinese invaded.

It was said that Chophel was charged with committing financial crimes (including producing fake banknotes). No counterfeit notes, however, were reported to have been found during a search of his home following his arrest. In his writings, Chophel had implied that it was perhaps the British who might have written to members of the aristocracy in Lhasa, notifying them of his activities, including being associated with the pro-China Tibet Improvement Party, a political party founded by a group of progressive Tibetan exiles in Kalimpong, where he was once based. There was no serious proof of his involvement in the party, except for the fact that he had helped design the party’s logo. Chophel’s black box, in which he had deposited some of his writings, was never found after his imprisonment.

Anyone writing about Tibet would know that Tibetan studies is a difficult, rich, vast, obscure, and above all a lonely and contradictory field. Any Tibetan writer worth his or her salt is forced to carry the burden of this spectacular legacy—made even more challenging because of the lack of institutional support owing to Tibet’s predicament as a lost land. And it is no surprise that many dedicated Tibetan writers and poets, especially the best of them such as Chophel, would fail to live beyond the age of 50. There is also something to be said about the challenges of swimming so strongly against the political current, but the courage and the intellectual stamina of these larger-than-life and brilliantly eccentric personalities would invariably provide great subjects for historians and even novelists. Chophel, for instance, partly served as the inspiration for one of the main protagonists, a world-renowned scholar, in my novel The Tibetan Suitcase.

Tsering Namgyal is the author of The Tibetan Suitcase: A Novel. Previously based in Hong Kong, he is currently based in Dehra Dun, India.