This article is also available in Russian (Эта статья также доступна на русском языке здесь).

Buddhism is not the largest religion in Russia: only about 1 per cent of Russians identified as Buddhists as of the mid-2000s. However, Buddhism has long occupied an important place in Russian culture, which has contributed a number of outstanding Buddhist figures to the world.

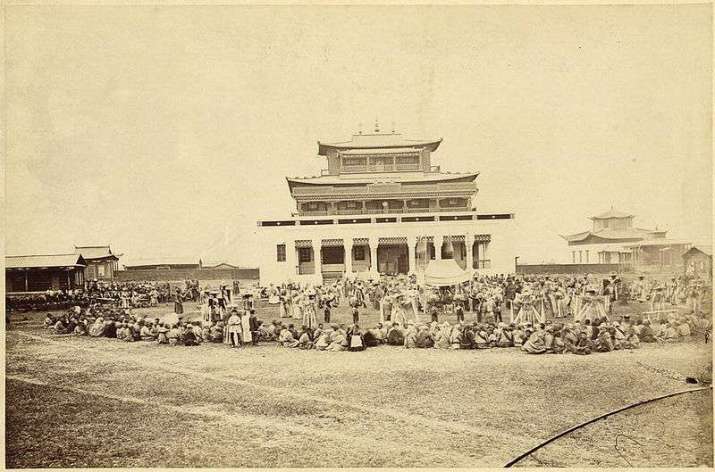

Buddhism appeared in the Russian empire early in the 17th century, when some Kalmyk tribes, who followed the Gelug school of Tibetan Buddhism, adopted Russian citizenship. However, the main center of Buddhism would become Buryatia, where Buddhism entered Russia from Mongolia. At first people gathered in prayer tents, but in the 18th century the first permanent monasteries, Tsongolsky and Gusinoozersky, were built. It is noteworthy that the first Buryat temple buildings were constructed with the help of Russian carpenters and therefore resembled Christian churches.

Buddhism spread in Russia in a unique fashion because the government actively united disparate communities into a single sangha,beleiving that it would be easier to deal with one key figure (given the title khambo lama) than with dozens of rival abbots. In addition, given Buryatia’s position on the border with Qing dynasty China, it was important for the government to control the foreign religious ties of the Buryats.

Another important feature in Russia was that Buddhism encountered another major world religion: Christianity. It is interesting to note that government policy toward Buddhists in the regions of Kalmykia, pre-Baikal, and Transbaikalia differed. In the first two cases, it was tougher, while in Transbaikalia, the tsarist government acted more cautiously because it was a border area where any unrest was undesirable. The authorities had to support the Buddhist sangha, sometimes even to the detriment of the interests of Russian Orthodox Church missionaries, who sought to Christianize the Buryats.

In 1853, the “Law on the Lama Clergy” was adopted, a legislative act regulating the activities of Buddhists in the Russian empire.

Buddhism has had a great influence on prominent Russian scientists, philosophers, writers, and artists, notably: Vladimir Soloviev, Nikolai Berdyaev, Nikolay Lossky, Leo Tolstoy, Ivan Bunin, Velimir Khlebnikov, Maximilian Voloshin, Nikolay Gumilev, Nicholas Roerich, and others. Through their works and others, the Buddha’s teachings became part of Russian culture.

An important stage in the further spread of Buddhism in Russia was the construction of a Buddhist temple in St. Petersburg in 1915. One of the initiators of the construction and its first abbot was Buryat Agvan Dorzhiev (1854–1938), a prominent public figure and diplomat, and one of the teachers of the 13th Dalai Lama.

Aghvan Dorjiev was one of the ideologists of the Renovationist movement (obnovlentsy), which advocated the modernization of the sangha. After the 1917 revolution, reformers tried to draw parallels between the ideas of Marxism and early Buddhism in order to save it.

A little earlier, another famous Buryat, Lubsan Sandan Tsydenov, tried to revive the tantric tradition in Russia. Together with several disciples, he went into the forest to found a community engaged in Buddhist practice. In 1919, he proclaimed the creation of the Kudun theocratic state. Interestingly, although it was an Eastern Buddhist theocracy it nevertheless featured a kind of parliament of the European sort.

During the anti-religious campaign of the 1930s, almost all of the Buddhist temples in the country were closed and many lamas arrested. In 1946, Ivolginsky and Aginsky monasteries were opened for political reasons—aiming to show that there was freedom of religion in the USSR. However, the authorities closely monitored all religious activities.

Despite this, Buddhism did not completely disappear. One of the brightest personalities of this period was Bidiya Dandaron (1913–74), a follower of Tsydenov, a famous Buddhologist and thinker. Dandaron tried to revive the tantric tradition in an atheist state. His students were from all over the Soviet Union. Dandaron also developed the concept of Neo-Buddism, a synthesis of Buddhist teachings with Western philosophy and the latest scientific theories. However, he was eventually arrested for creating a religious community, and died in a prison camp. Yet his disciples played an important role in the revival of Russian Buddhism in the 1990s.

The true restoration of Russian Buddhist institutions became possible in the late 1980s. This process included the construction of temples, the translation of religious literature, training new monks, and establishing channels of contact with centers outside of Russia. Numerous communities of lay Buddhists, including women’s groups, emerged. Prominent teachers such as the 14th Dalai Lama, Kushok Bakula Rinpoche (1917–2003), The Ninth Bogdo-gegen (1933–2012), and others played important roles in this revival.

As a result, Buddhism has since been proclaimed to be one of the traditional religions of Russia along with Orthodox Christianity and Islam. In 2016, there were 259 registered Buddhist organizations, most of them lay Buddhist centers. While there was a single official organization—the Central Spiritual Administration of Buddhists—before the dissolution of the USSR, believers have since become divided along ethnic and national lines. Today, the Buddhist Traditional Sangha of Russia represents the Buryats; the Kalmyks created the Association of Buddhists of Kalmykia (1991), and in Tuva there is the Union of Buddhists of Tuva. The vision of what Buddhism should be has also changed.

Buddhism in Buryatia

The official position of the Buryat sangha was expressed by its new khambo lama, Damba Ayusheev (elected in 1995). He expressed a belief that Buryat Buddhism is an independent branch of Buddhism that is opposed to Tibetan influence.

In 2002, the grave of the 12th Khambo Lama Itigelov (1852–1927) in Buryatia was opened, following the instructions in his will. The body within had not significantly decomposed, and was thus declared to be imperishable. Itigelov became a religious phenomenon on a national scale and the body is now located in the Ivolginsky datsan, a Buddhist temple in Buryatia, and is exhibited for believers to worship several times a year.

In 2005, Khambo Lama Ayusheev announced the discovery of the face of a goddess on a stone in the Barguzin valley. The godess was later identified as Yanzhima (Skt: Saraswati). In Indian mythology, Saraswati is a sacred river that disappeared underground, and should return in better times. The appearance of the face of Saraswati in Buryatia was interpreted as a sign that the locus of spirituality was shifting to the north.

The imperishable body of Itigelov, the appearance of Sarasvati, and other relics have created a new sacred geography and history, connecting Buryatia directly with ancient India and bypassing Tibet. This is a local attempt to justify the independence of Buryat Buddhism and to prove its identity and self-sufficiency.

However, in addition to the traditional sangha in Buryatia, there are other Buddhist communities. These include followers of Dzogchen and other schools. One of the key figures of Buddhism is Eshe Lodoi Rinpoche, a tulku and the holder of the highest Buddhist degree of geshe lharamba. In 2004, he founded a monastery in Buryatia called Rinpoche Bagsha.

Buddhism in Kalmykia

There are currently 27 temples and monasteries in the territory of Kalmykia. The Kalmyks historically maintained stronger and more direct ties with Tibet—a tradition that continues to this day.

In 1992, Telo Tulku Rinpoche became the head of the Kalmyk sangha. From a family of Kalmyk emigrants to the United States, he studied at Drepung Gomang monastery in India, where he was recognized as the reincarnation of the famous yogi Tilopa (988–1069). Since 2014, he has been the honorary representative of the Dalai Lama in Russia and Mongolia. In 2005, the new main temple of Kalmykia, the Golden abode of Shakyamuni Buddha was opened, becoming the largest Buddhist temple in Russia and Europe.

Unlike his Buryat counterpart, Telo Tulku serves as a link between the Dalai Lama and Russian Buddhists. He helped in the organization of the dialogue between Russian scientists and the Dalai Lama, and has drawn on that relationship to bring the noted Buddhologist Robert Thurman and other prominent Buddhist figures to Russia.Unlike his Buryat counterpart, Telo Tulku serves as a link between the Dalai Lama and Russian Buddhists. He helped in the organization of the dialogue between Russian scientists and the Dalai Lama, and has drawn on that relationship to bring the noted Buddhologist Robert Thurman and other prominent Buddhist figures to Russia.

Buddhism in Tuva

The first Buddhist monasteries in Tuva appeared in the 18th century. Until 1912, Tuva was under Manchurian rule and Tuvan lamas were subordinated directly to the Bogdo-gegen in Mongolia. As in Buryatia, Buddhism coexisted with the local shamanist tradition. By the end of the 1920s, there were 19 temples in Tuva and about 3,000 lamas. But by the early 1940s, all of the temples were shut down and soon destroyed, and the lamas were repressed. However, a revival of the Buddhist community in Tuva began in 1990.

Lay Buddhists

In addition to organizations that unite Buddhists on ethnic and national grounds, there are many communities of lay Buddhists in Russia that unite around a teacher and/or Buddhist school. In general, these are people who consciously adopt Buddhism in adulthood.

The largest such community was formed by followers of the Danish teacher Ole Nydahl: the Association of Buddhists of the Diamond Way of the Karma Kagyu tradition. There are now almost 100 centers in this tradition across the country. Along with religious activities, this organization carries out serious cultural, scientific, and educational activities, holding lectures, exhibitions, and scientific conferences.

Another example of a lay Buddhist community is the Ganden Tendar Ling Buddhist Center in Moscow, established in 2001, a branch of the international Foundation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition (FPMT). There is also an Aryadeva Buddhist group in St. Petersburg that represents the FPMT. Both belong to the Gelug tradition. The center is engaged in teaching Buddhist theory and practice, translation and publishing work, as well as charitable activities.

The activities of other communities are generally similar: practical classes, translation, and so on. In many ways, it is the lay communities that form the face of Buddhism in Russian society, as they unite the most educated, active, and motivated followers, publish a significant amount of literature, and organize various events.

In addition to Vajrayana Buddhism in Russia there are also followers of Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and Vietnamese schools of Mahayana, as well as Theravada Buddhism.

References

Bernstein, Anya. “The Post-Soviet Treasure Hunt: Time, Space, and Necropolitics in Siberian Buddhism.” Comparative Studies in Society and History 53, no. 3 (2011): 623-53.

Ламаизм в Бурятии XVIII — начала XX века: Структура и социальная роль культовой системы. Новосибирск, 1983. (Lamaism in Buryatia of the XVIII-early XX centuries: the Structure and Social Role of the Cult System. Novosibirsk, 1983.)

Цыремпилов Н. В. Буддизм и империя: бурятская буддийская община в России (XVIII — нач. XX в.). Улан-Удэ, 2013. (Tsyrempilov N. V. Buddhism and Empire: Buryat Buddhist community in Russia (XVIII-early XX century). Ulan-Ude, 2013.)