In an era of 24-hour access to sensationalist headlines, there is the risk of becoming overwhelmed, and yet there is also the reality of news of genuine concern. Climate change and its effects on weather, natural resources, migration, and the long-term habitability of the planet are some of the most stirring and serious issues in our contemporary era.

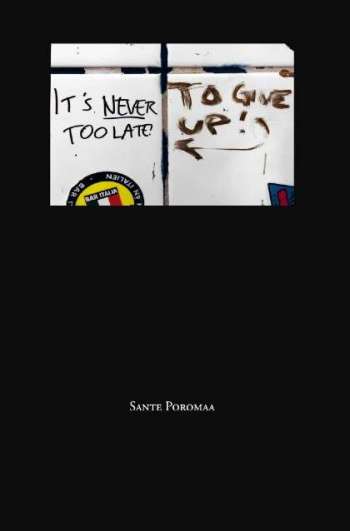

In his new book, It’s Never Too Late—To Give Up! (Zendo Publications 2019), Zen teacher and author Sante Poromaa looks at the prospect of civilizational collapse squarely, without hypothesizing or issuing demands. He discusses responsibility and social engagement from a Buddhist perspective, as much as he addresses more philosophical Buddhist concepts like anicca, impermanence. Poromaa also brings attention to this ‘Anthropocene’ era in a succinct yet also expansive way—the various text and project references he lists are numerous and fascinating.

A Zen teacher at Zengården in central Sweden, Sante Poromaa is originally from Kiruna, a city in Arctic Sweden. Poromaa began practicing Buddhism with Philip Kapleau Roshi in 1982. The Zen Buddhist Society, the largest Zen Buddhist organization in Scandinavia, was founded in 1982 during Kapleau Roshi’s visit and Zengården and officially opened in 1990. Poromaa has been teaching since he received Dharma transmission and permission to teach in 1998 by Philip Kapleau Roshi’s successor, Bodhin Roshi. He became a Buddhist priest in 1991.

Buddhistdoor Global sat down to talk with Poromaa about the central themes of his book It’s Never Too Late—To Give Up!, Zengården as a community, impermanence, cyclic versus linear thinking in the West, and more.

BDG: In It’s Never Too Late—To Give Up!, you note that “Zen, as a tradition within the greater Buddhist field, also provides a worldview which can incorporate hopelessness and despair as meaningful parts of the path.” (74) What is Zen’s specific offering, among Buddhist traditions, to incorporate these experiences of angst and despair into practice?

SP: The teaching on Impermanence and of giving up destructive desires is something that is shared by all Buddhist schools. So Zen is not unique in that. But perhaps the Zen practice of insistence on presence and “being-here-now” can be helpful.

BDG: Zengården serves as a Zen Buddhist retreat and training center as well as a hub for people to come together, create communal support and cultivate local sustainability. Such practices help to create community as well as can contribute to a more ecologically sound path which could perhaps be key to survival in uncertain times. What are your thoughts on communities developing the means and resilience to not only survive but also possibly thrive through uncertain times?

Image courtesy of the author

SP: It depends of course on how difficult times will get. But it seems clear to me that a community like Zengården will need to b embedded in a larger community (village) in order to survive. This takes forward planning around issues like energy and food production. Zengården will work to install geothermal heating and solar panels and increase the amount of food we grow ourselves.”

BDG: I really appreciated the “Housekeeping” chapter and the description of cleaning, from a spiritual point of view, as an opportunity to be liberated and relieved of self absorbed thoughts. You insightfully point out that “Even in feminist discussions . . . there is a lack of appreciation for the act of cleaning itself.” (53) This is a fascinating point. Zen seems to, among many traditions in fact, have a unique relationship to cleaning as integral part of practice. Why is this?

SP: I don’t know about other traditions but in Zen it is certainly part of the practice. And it isn’t just about cleaning, but in a more general way about not separating yourself from your environment and seeing truth in every little thing you encounter—treating everything with respect. This is because we’re not separate, and the mistaken idea that we are is a basic cause of suffering.

BDG: How does Zengården, as a community, work to have a smaller ecological footprint- both as a collective and by individual residents and retreat goers?

SP: People living in a communal style generally use less water, electricity and so forth than people living alone or in small families. We only serve vegan food, try to buy locally that which we can’t grow ourselves and we are in general very careful about things like no waste, reusing things, avoiding plastic when it’s possible. The way we live at Zengården I believe affects the people coming there (for example, we practice veganism), which then hopefully spreads to society in general.

BDG: You note that according to Buddhist tradition, the Dharma end-times are around year 2100. (42) Just to check, this is according to “The Scripture Preached by the Buddha on the Total Extinction of the Dharma,” correct? Does the total extinction refer to both Dharma and humanity? Are they assumed to be interwoven?

SP: The 2100 prophecy comes from several sources. These sources suggest that the Dharma will go through five phases ending in something called mappo in Japanese (end of Dharma). These periods are often said to be 500 years long and it starts with the time of the Buddhas life (somewhere between 500 and 400 BCE). That would bring mappo to around year 2100.

Whether the end of Buddhism means the end of human civilization is unclear, but it might happen. It doesn’t suggest that the human species would go extinct, though.

See more