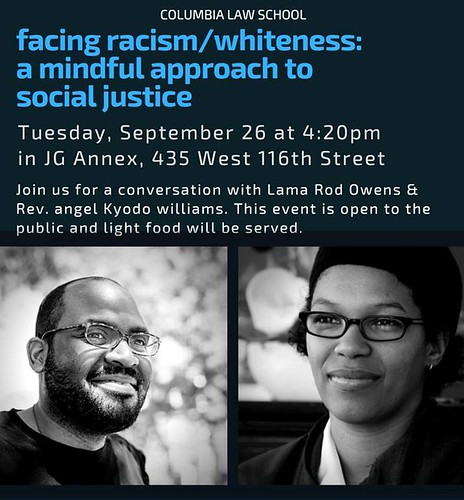

Growing up in a southern Black community, cultivating resilience was intrinsic to Rod Owens’ lived experience. In the midst of segregation, prejudice, and racially based violence, getting knocked down and getting back up again has been deeply conditioned in his family and community for generations. Now an authorized Kagyu teacher and author, with a Master of Divinity from Harvard University, Lama Rod Owens shares his thoughts on growing up Christian and becoming a Buddhist lama.

Owens shared that as a child, inspiration came from Christian theology: to be good and virtuous in the world, one must experience suffering as Jesus did. “Having grown up in church, we were taught that we were children of God. When people know that, their experience is very different. We see more than our own suffering and we could show up in a more open, loving, vulnerable way.”*

The reward was found in Heaven after death. But Owens remembers feeling: “I didn’t want to wait—I wanted heaven now! I didn’t want to just suffer during this life—I didn’t believe in suffering.” He felt there had to be a solution during this lifetime, and didn’t believe that just because he was born Black he had to suffer.

The basis of his burgeoning interest in social justice formed early. The resilience of his community and ancestors kept him going. Owens was fortunate to have a mother who encouraged him to be community-minded by her example. As a minister she was always organizing health fairs, mentoring women’s groups, and so on. Owens was deeply influenced by her activities and as he got older was inspired by her—he began to feel called to the path of service.

Facing racial injustice and other challenges, Owens has often worked with the question of how to sustain himself. He has been deeply inspired by such civil rights champions as Audre Lorde, who said, “Caring for myself is not self-indulgence, it is self-preservation, and that is an act of political warfare.”** When a marginalized person preserves themselves, they are disrupting the very systems that want them gone. Owens wanted not merely to survive, but to thrive in spite of these systems.

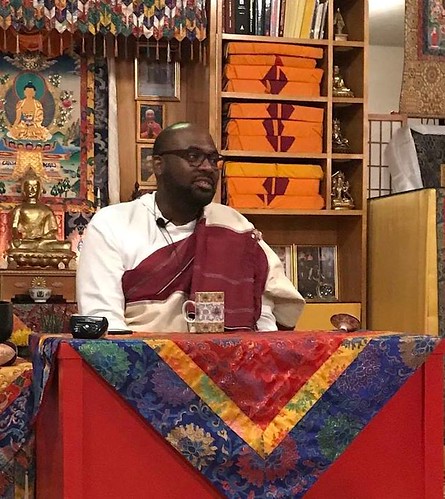

For true resilience one must not only survive societal violence, but learn how to cultivate connectedness and stability within survival. Self-care becomes a crucial factor. Citing another hero, James Baldwin, Owens offers the reminder that, “If you don’t rest then you won’t survive the war.” So rest is central to his self-care and resilience. His three-year retreat was the pinnacle of the deep grounding he needed to cultivate a lifelong allegiance to rest—in the silence, the practices, letting go of unhealthy and toxic thoughts and patterns. Owens credits his three-year retreat for his current resilience, along with his upbringing. His teacher, Lama Norlha said: “If you can survive retreat, you can survive anything!”

I asked Owens how, as a black man in our current society, he cultivates the tools to support his own mind, his students, and his work? He shared that he has learned to not take himself so seriously, recognizing the illusory nature of self. If someone calls him a name, he feels that they don’t know who he is and they don’t know who they themselves are, their own innate wisdom or Buddha-nature clouded by ignorance. By enacting violence on another, an aggressor enacts their own self-violence. If we can relate to and rest back into our own nature, we can alleviate the hurt we cause and receive.

We need to learn to refrain in order to rest. We are overly engaged in non-meaningful activities. If we can refrain from constant email and social media and be alone, be silent, and limit the distractions, then we can restore. Owens calls this basic rest. Resting, letting go, being still are not the same as sleeping! We only keep what sparks joy (Marie Kondo style!)—and this includes activities and company, not just the things in our environment. Joy is a key aspect of resilience, and humor is also important as an expression of what’s happening in the moment—not as an attempt to hide or perform something, but to make people feel comfortable and to articulate in the moment. Humor helps spark joy and disarms people to let a transmission come through, releasing others to be themselves.

Following his three-year retreat, Owens had to undergo the process of finding his authentic expression as a Western, Black, poly-queer lama. His article for Lions Roar on intersectionality helped express how many practitioners can authentically relate to all locations of their own culture, race, class, and sexuality distinctions within their Dharma communities.***

Owens says his teacher gave him a lot of agency to be himself in the world, and he drew confidence from that in the ways he now teaches and embodies the Buddhadharma. Due to his upbringing, character, and long retreat, the more intense the world becomes, the happier Lama Rod feels. It is a sense of feeling in the right place and time to give what he can offer. He points to advanced practitioners being called to hold space now in the midst of such global strife and intensity. This crazy, violent modern world illusion is very real, but if we can straddle extremes, we can create a profound and fierce way of being in the world, caring for ourselves and for others.

In 2016, Owens co-wrote the book Radical Dharma, with Reverend angel Kyodo williams and Jasmine Syedullah, about social justice and their roles as black teachers in deconstructing societal systems of suffering, in the context of modern Buddhism, to be truly inclusive. The Dharma is evolving and its models and expressions are therefore changing. Seeing the value in this is crucial for true inclusion. We must ask, what is the evolution of the basic Dharma teachings? How do they begin to take on the essence of particular identity groups? What does that look like? Radical Dharma opened a door for Owens to experience authentic personal and group expression, and to cultivate confidence in these.

Owens puts it eloquently: “It takes more of us honoring who we are instead of erasing parts of ourselves to fit into our lineage culture. I may or may not be recognized by my lineage if I express my authentic self. Sometimes being ignored is a gift because I have the agency to make my own choices—to make things happen and establish my own brand. I am still part of the authentic lineage, but if it’s just hard and not joyful, then we must ask, are these ways of teaching outdated that don’t connect to people here and now? What is the best way that expresses who we are, and what the Dharma is for us, here and now? We all need the Buddhadharma, yet it needs to evolve in its manifestations and methods in order to reach the diversity of practitioners in the West.”*

* Video interview, 22 January 2019

** Self-Care Is An Act Of Political Warfare (HuffPost)

*** Do You Know Your True Face? (Lion’s Roar)

See more