More dances are associated with Buddhism than any other religion, from the cool elegance of Japanese Noh theater to the gyroscopic monsters of Vajrayana Buddhism, high in the Himalaya. Buddhism has transformed both. Our understanding of dance should be broadminded, whether dance is an acrobatic language and high modern art, or something ancient, magical, and consciousness-altering; whether a continual source of the new and groundbreaking, or the living reality of the ancient. Buddhism is and has been a leavening agent across borders and art forms. Western choreographers of the 20th century revolutionized Western dance through their adoption of Buddhist principles applied to their own artistic practice.

Buddhism, by its very nature as a world religion without a central ecclesiastical authority, without a binding religious orthodoxy, and without any attempt to eliminate cultural distinctions, introduced artists to new realms of thought and offered a transcendent unity, a linked cohesion to far-reaching spiritual consciousness. Buddhism burst the boundaries of social conventions, and informed artists that they belonged to a larger cultural arena and had a role within it. The awareness of Buddhism’s syncretic facets gave a freedom to artists, often raising their art to unprecedented heights. The choreography of 20th century masters Anthony Tudor in classical ballet, and Merce Cunningham in modern dance give ample testimony to this idea of Buddhism’s leavening agency, just as do Japanese Noh and Himalayan monastic Cham.

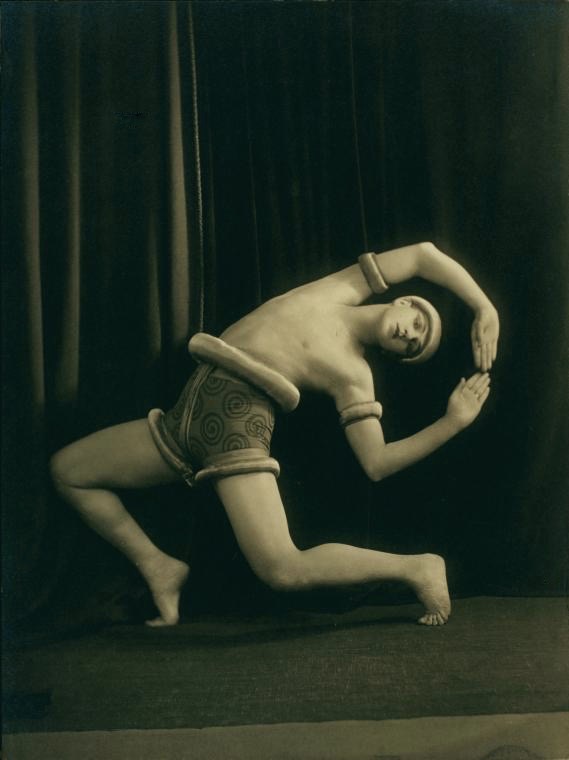

Image courtesy of the New York Public Library,

Jerome Robbins Dance Division

One of the most fundamental Buddhist concepts is the impossibility of expressing in words that which is most real, sublime, and ultimate. Supra-verbal transmission is at the heart of Buddhist transmission and practice. Compassion, unlimited tolerance are essential principles. Buddhism easily adapts to alien ways of thinking and making art without sacrificing basic concepts. Buddhism has adapted to native creative traditions, at the same time transforming them by presenting a challenge of expansive thought that brought out their latent possibilities and led artists to make a creative response.

Since Isadora Duncan’s observation that something was missing from Western dance, generations of Western dance artists have searched themselves, cultural history, foreign lands, and spiritual concepts to find that lost piece and to express it. The missing piece is gnostic creativity. Quite unlike Buddhism, Christianity over the centuries systematically suppressed dancing and asserted religious justifications. The philosophies of the Enlightenment emphasized reason over feeling. Buddhism has no such desire to control, even as different types of Buddhism have produced different types of dance.

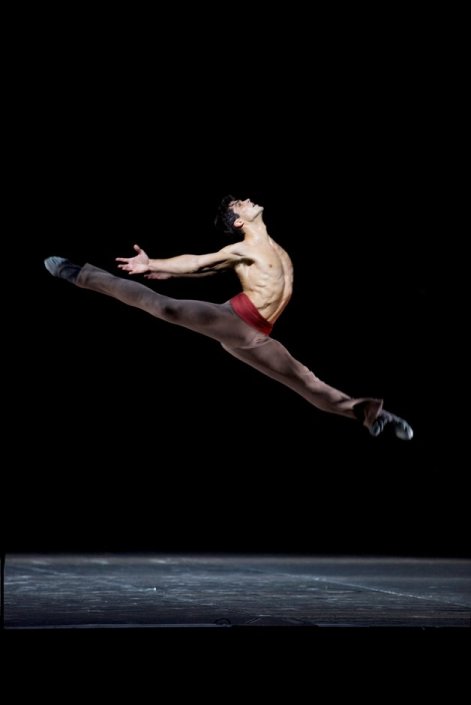

The Leaves Are Fading, 1975. Photo copyright Vanja Karas

Buddhism’s journey across the globe and across millennia has been one of growing assimilation, endless varieties of expression, and spiritual transcendence. It is not by accident that the unlimited time and empty space of Buddhist metaphysics should appeal to independent artists unsatisfied with incomplete notions of dance, and restrictive societal norms that stifle artistic expression. Buddhism is about perceptive refinement and the person as locus of spirituality. The body is the vessel of enlightenment. This basic idea, foreign, even an anathema, to Western philosophies, set fire to creativity, self-realization, and a breathing spiritual reality.

Dance is a civilizing agent bringing order, a living talisman of cosmic propriety. Buddhism is a refining discipline. When civilizations meet and interact in high-minded harmony, there comes the sheen of mutual respect, an embracing light on the edge of creation. Some cultures and cultural forms are more amenable than others to syncretic development. Still, civilizations meet in individuals. A succession of 19th and 20th century Western dance artists encountered, explored, and practiced Buddhism, deeply affecting their own creative work and leaving a changed idea about both dance and Buddhism.

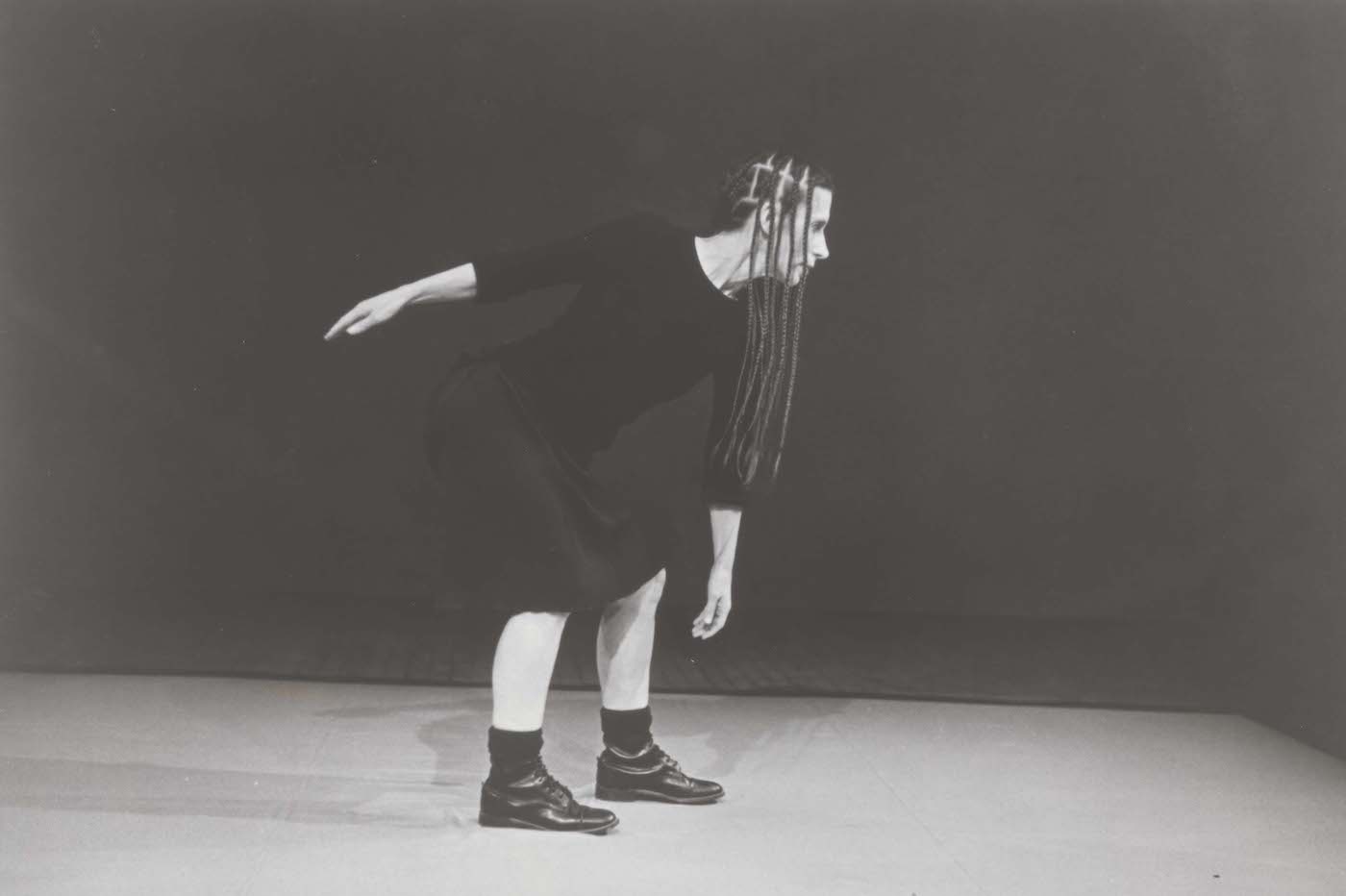

The stretch of a century, the 20th century, added to Buddhism’s eons, provides an opportunity to appreciate the qualities of Mind and personal character among those adventurous artists who experienced pioneering encounters with Buddhism’s power to inspire and invigorate the transformation of their artistic practice. Within the field of Western theatrical dance, great artists embodied and exemplified transformation by Buddhist principles. Among these are dance pioneer Ted Shawn (1891–1972), ballet choreographer Anthony Tudor (1908–87), modern dance master Merce Cunningham (1919–2009), and avant garde creator Meredith Monk (b. 1942).

The experiences of these dance artists were part of a larger wave of nascent Western Buddhism, a new phase of something Buddhism has always done: assimilate. Their work is the expression of their enlightenment, initiated by travel, research, intuition, and artistry. Buddhism’s pattern of providing expansion at the edge of personal freedom, coupled with a dancer’s fascination with the choreographic unknown, sets the stage for the liminal trans-historical to interact with the liminal personal creative, and produce a transgressive poetic. Putting a lens to dance and Buddhism is to see what occurs where the liminal meet. It is a study of going beyond.

Dance artists Shawn, Tudor, Cunningham, and Monk embody the transformative potential of Buddhism. Their examples prove that creativity cannot be duplicated, and the result of Buddhism’s expansive influence on dance has been broadened horizons of expression, liberated personal freedoms, and the manifestation of principles. The application of Buddhist principles revealed new depths to their art.

Be inspired in the manner of Shawn, who realized that the core of danced expression was not theatrical but spiritual. Be inspired in the manner of Anthony Tudor, who realized that Zen was “just this” even in 1920s London, bereft of anything Asian or symbolic. Be inspired in the manner of Cunningham, who honored the unadorned moment as pure, and the splendor of the phenomenal world coming together, as the unrepeatable voice of the cosmos; or by Monk, who creates entirely new forms of music and movement that speak universally. Personal growth and artistic practice can be transformed by Buddhist principles. My wish for you as we begin 2021 is simple: Be Inspired.

See more

Related features from Buddhistdoor Global

Dance in the Reality You Have

Self-reflection in Kashmir

When Dance Transforms