The transience of life is understood and expressed in different ways within Buddhism, perhaps nowhere more sensitively than in Japanese performance literature of the Kowaka and Noh theater traditions. Zeami, the 14th century performer, playwright, and theorist who established Noh as we know it today, was asked, “What is the essence of transience?” He answered: “Scattering petals, falling leaves.” When asked, “What is the essence of eternity?” He answered: “Scattering petals, falling leaves.”

The Kowaka version of the story of young samurai Atsumori, is an authentic taste of Samurai life—living with the spiritual reality of imminent death. In the Noh version, the ghost of the slain Atsumori returns to confront his enemy, only realizing in the Buddha that there are no enemies.

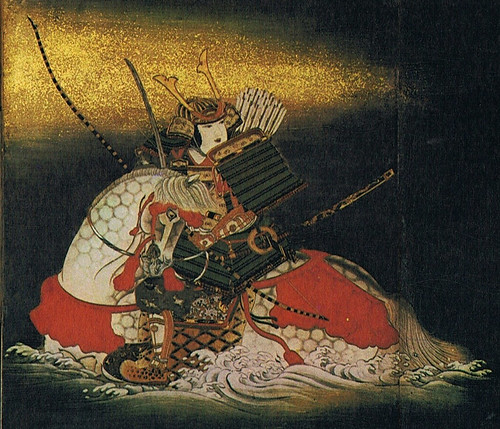

The use of poetry to indirectly suggest seasons, cosmic cycles, religious truths, and personal situation is a characteristic of Japanese classical poetry. The tragic tale of young Atsumori of the Taira clan, a noble and refined youth who fell at the hands of the renowned samurai Kumagae of the Minamoto clan, is bittersweet for its extolling of refinements, profound changes of heart, and death at so young an age, merely 16.

Victoria and Albert Museum. Photo by Jonathan Greet

The facts are true and simple. In the 12th century, Japan was in the throes of civil war, pitting the ruling Taira clan against the Minamoto. The Heike Monogotari, or Tale of the Heike, recounts the fateful battle of Ichi no Tani at Sumo Bay, where the Minamoto routed the Taira, who fled back to their departing ships.

Young Atsumori, a courtier praised as the finest flute player and so possessor of a rare and excellent flute, noticed that he had dropped his flute while returning to the ships on horseback through the roaring waves. So he retuned to retrieve it. In this, his youth, his naiveté, and his refinement are apparent.

Fatefully, he encountered none other than the most ferocious and fearsome warrior, Naozane no Kumagae, master samurai of the Minamoto clan. It is this encounter in the surf, between young noble Atsumori and seasoned martial artist Kumagae, that is retold in the literary traditions of two distinct Japanese performance forms, the archaic samurai entertainment, Kowaka, and later, the rarified multi-artform Noh theater.

The Kowaka tradition places a Buddhist framework on the tragedy—an historically true one—where the Noh play takes Buddhism a step farther, when the samurai-turned-monk encounters the ghost of Atsumori to re-enact the battle.

He looks behind and sees

That Kumagai pursues him:

He cannot escape.

Then Atsumori turns his horse

Knee-deep in the lashing waves,

And draws his sword.

Thrice, three times, he strikes,

Then, still, saddled,

In close fight they twine

Rolling headlong together

Among the surf of the shore.

So Atsumori was slain

But now the Wheel of Fate

Has turned and brought him back.

(Atsumori, by Zeami, 14th century. Translated by Arthur Waley, Chas. E. Tuttle Co., 1921)

The codes of samurai conduct were established and well known; honored and carried out as rules of warfare. Picture this: a large ferocious warrior with his foot holding down a beautiful young man in the shallows of the water. They each know of the other by reputation, but neither realizes who he is fighting, and so, according to custom, Kumagae asks young Atsumori his name. Atsumori replies, “Behead me as you must. Take my head to the leader of your clan and ask my name.”

Kumagae at length learns it is the elegant and educated courtier Atsumori. The samurai protocol breaks down. Kumagae sees no enemy, but a refined young man, more mature and worthy than his own son, and the karmic entwining of their lives by his killing the boy is a spiritual realization that the warrior, for once in his life, cannot bear.

But the boy will have none of it, as battle rages around them. Both are expected to behave as samurai, and for only that high principle of life did Atsumori enter battle, his very first. Atsumori would live and die as an example of honor. And so, agreeing to their karmic destiny, Kumagae beheads Atsumori, only after vowing to leave the military life, to become a monk and pray for Atsumori’s escaping the Wheel of Life and Death. He returned to his chief and delivered the head.

Upon seeing the head displayed, Kumagae’s worldview disintegrated, vanishing like all fleeting things of this world. Indeed, their karma had been sealed during the battle exchange, but this bond would continue, evolve, and heal. The mighty Kumagae left the life of the literati and samurai for that of a monk. He entered Kurodani-ji, a temple in Kyoto, took the priestly name Rensho, and there prayed for Atsumori’s arrival in the Tushita heaven.

Later in life he made the pilgrimage to the sacred mountain Koya San, where he interred Atsumori’s ashes and built a temple to their eventual unity in the Buddha, when, joined in enlightenment, the two would be united in the One Lotus.

If I were to remain with others in the world of sorrows, I Kumagae, would experience again such moments of grief. I have become aware that this world is not a permanent abode, aware that this life is less certain than beads of dew on leaves and grass, or the reflection of the moon that dwells on the water. One may poeticize the blossoms of Kyoto, but flourishing blossoms are the first to be swept away by the winds of impermanence. Those who enjoyed the moon from the South Tower were stolen away beyond the clouds even before the clouds hid the moon from view. (Atsumori, a Kowaka narrative, paraphrased from The Ballad-Drama of Medieval Japan by James Araki, Chas. E. Tuttle Co., 1964)

Kowaka was a military entertainment, simply performed by standing, walking, stamping, all of which punctuate the telling of a Buddhist martial story. Ancient ways of warfare were imbued with a sense of honor. The samurai fought according to one honorable code. They knew that tomorrow’s battles would bring death to their group. Not everyone would return to camp. The tragic story of Atsumori was one such tale told on the eve of battle. It was to remind the samurai of the transience of life, the honor of living, and Buddhist transcendence awaiting all.

Photo by Jonathan Greet

See more