Venerable Chaofan (超煩) is the founder of American Association of Buddhist Education (美國佛教教育協會) at Fuhui Temple (福慧寺), which is situated in Rancocas Village, Westampton, New Jersey. Originally from Inner Mongolia, Ven. Chaofan was ordained in 1981 at Mount Wutai and became one of the first graduates of the Chinese Buddhist Academy in 1986. After working for Buddhist organizations in China and pursuing further studies in Sri Lanka, he relocated to the United States in 1996. In this interview, Ven. Chaofan shares his experience of, and views on, Chinese Buddhism in the US.

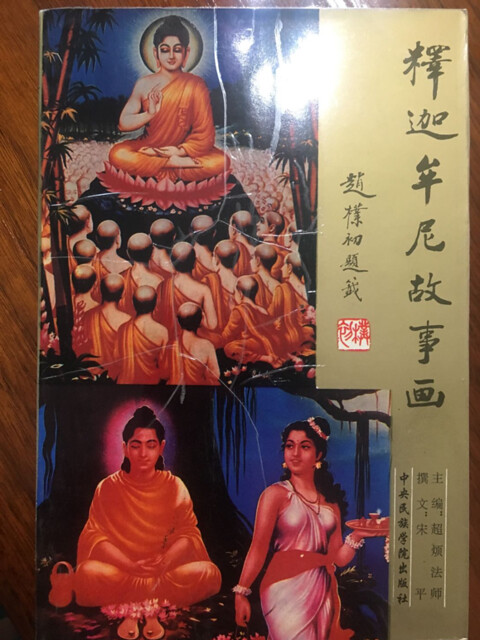

Image courtesy of Ven. Chaofan

Buddhistdoor Global: Since you moved to the United States in 1996, you have witnessed the development of Chinese Buddhism there. In your opinion, what achievements has Chinese Buddhism made and what difficulties has it encountered?

Venerable Chaofan:The first generation of Chinese sangha in the US arrived in the 1960s. Among them, Venerable Master Hsuan Hua (宣化) built the City of Ten Thousand Buddhas on the West Coast with his own hands. He set up Buddha images and taught a wide audience including local American disciples, which symbolizes the advent of Chinese Buddhism in America. On the East Coast, there were Venerable Shouye (壽冶), Venerable Ledu (樂渡), Venerable Minzhi (敏智), Venerable Haolin (皓霖), and Venerable Fayun (法雲). Likewise, they established Dharma centers with little support, except for the Buddhist traditions they inherited and their virtue of great compassion. The first generation of Chinese sangha united overseas Chinese and helped them to obtain social respect. They also managed to translate Chinese Buddhist classics into English, which was fundamental for Americans to delve deeper into the Buddhadharma. The harship the first generation encountered were very similar to those encountered by ancient masters during the early development of Buddhism in China.

The second generation arrived in the eastern US in 1990s. Similarly, they had little political or financial support; nor did they have any existing following. Some of them inherited Dharma centers from the first generation; some totally relied on themselves to create a community. They promoted cultural exchange and mutual learning between the East and the West, thus promoting the advancement and development of human civilization. Through cultivation practice, they spread Buddhist beliefs and ideas, contributing to the harmony and peace of the world. Among both the first and the second generations, the custom of one monastery-one monk persisted. Some monasteries have two or three monastics, in which case they came and went. This was particularly the case in the US where freedom is emphasized.

The monastics and laity who arrived after 2000 belong to the third generation. They built monasteries and various kinds of Buddhist organizations around Chinatown in New York. Some are genuine, while the motives of some are dubious. In some cases, they even impair the tradition of Buddhist culture and faith.

BDG: The so-called American Buddhism took inspiration from Theravada, Tibetan, and East Asian traditions. What do you think of such a synthesis? When it comes to the promotion of the Buddhadharma, do you think each school should stand steadfast to their traditions, or should one take the initiative to reform and innovate?

VCF: Though the three canonical collections developed separately, respectively in Chinese, Tibetan, and Pali, they all derive from the teachings of Shakyamuni Buddha. The three traditions have been passed on through different languages, writings, costumes, and ethnicities, but in truth such differentiation only betrays our deluded conceptualization. When the Buddha attained enlightenment under the Bodhi tree, the first words he uttered were, “All sentient beings have the wisdom and excellent characteristics of Tathagata, the dull-witted and ordinary ones are not able to understand the truth of the cosmos due to deluded conceptualization.” While integrating different schools, the development of American Buddhism should rely on traditional thought and innovative forms. My reasons are as below:

First, mind, Buddha, and all sentient beings are intrinsically one, with no difference. It is a truth regardless of time and space. The core concept of Buddhism, such as the rules of the precepts, should be adhered to. The essence of the precepts of the past, present, and future buddhas is immutable as vajra. On the other hand, the awe-inspiring manners, such as alms giving, monastic robes, Chan practice of farming, scholastic studies, localization, are all responses to the needs of the times.

Second, American Buddhism should advance the strengths and overcome the weaknesses of each of the three schools. For instance, in terms of Chinese Buddhism, we should put more emphasis on the preservation and development of the Five Sciences (wuming, 五明), particularly the science of medicine. Because medicine can eliminate the pains of sentient beings, including sangha members, therefore the science of medicine can guide sentient beings to Buddhism.

Finally, we should uphold the principle of separation of religion from politics. Buddhism is for self-cultivation. It should not be associated with politics and governments should not overly favor or honor monasteries. Even today, On Why Monks Do Not Bow Down Before Kings by Ven. Huiyuan (334–416) is worth referring to. Moreover, monasteries should restore public ownership to benefit society and all sentient beings.

Image courtesy of Ven. Chaofan

BDG: Could you please introduce the origin and mission of the American Buddhist Association of Education? So far the student body is only comprised of bhikshuni, how do you see the current situation of bhikshuni education? How can it be improved?

VCF: Originally, the Buddha taught moral standards and cause and effect to his five disciples and later sangha with the Three Dharma Seals, Four Noble Truths, Six Reverent Points of Harmony, Noble Eightfold Path, and Twelve Nidanas. The Buddha’s principle of “teaching without differentiating social classes” and “the world is of great harmony” stands for the pursuits of peace, compassion, and wisdom.

Therefore, on 3 December 1997, the second year after I moved to the United States, I registered the American Buddhist Education Association, Inc. with the federal government. To make it more accessible, we promote the Dharma through the affiliated Fuhui Temple (福慧寺). For instance, we regularly visit nursing homes every week, guiding seniors to recite the names of the Buddhas and providing hospice care.

As the organization became consolidated, we established the Buddhist Education Academy (美國佛教教育學院) on 31 December 2016, with two colleges respectively for bhikshu and bhikshuni. Each academic year is comprised of two semesters, one summer retreat, and a winter retreat. The curriculum focuses on the Three Great Classics of the Nanshan Vinaya School and the English language.

The mission of the academy is to carry on the Buddha’s compassion for all sentient beings, promote traditional Buddhist culture, improve the quality of monastics, foster international leaders within the Buddhist sangha, and advance world peace. So far, the conditions are only complete for the college for bhikshuni, so we have started its operations. The Buddha elucidated on the differences between male and female, and noted that females are more sensitive. Therefore, the reinforcement and regulation of Vinaya education for bhikshuni is conducive to the stability of the bhikshuni community. Nevertheless, we should have no notion of male, female, being, or lifespan, as the pure Buddha-nature is the same. There has been one sangha only. The separation of places of learning and practice for bhikshu and bhikshuni is intended to safeguard the peace and purity of the Dharma. It is also an essential precept in Buddhism.

BDG: You are well-versed in the Buddhist classics and you have traveled to many parts of the world. Looking back on your diverse experiences, who or what has motivated you the most, particularly in your career of promoting the Dharma in the US?

VCF: Shakyamuni Buddha gave up his country and kingship. In order to seek peace, compassion, and wisdom he went into the mountains to practice asceticism. This has been a reminder of what kind of thoughts should arise from my mind—I should not indulge myself or follow the crowd blindly.

From monastics in the ancient text Biographies of Eminent Monks to biographies of modern masters, they all focus on masters who abandoned fame and profit in the worldly realm. These masters regarded the precepts and suffering as their teachers and followed the footsteps of the Buddha toward the door of Nirvana. Every one of them are my Dharma friends (kalyāṇamitta) whom I emulate. For instance, 1,600 years ago Master Faxian traveled through the desert on foot at the age of 60, searching for Vinaya scriptures, and translated those texts at the age of 80. If this spirit is carried forward, there is no dream that cannot be realized.

Some lay Buddhists in the US are not that wealthy, but they spare no effort in supporting the Three Jewels, and in such a generous manner. When laymen and women respectfully offer their savings on their knees, my heart of repentance, transcendence, and compassion is strengthened, and my bodhi vows of repaying the four graces (from the Three Jewels, parents, motherland, and all sentient beings) and relieving three kinds of suffering (from external circumstances, impermanence, and consequences of action) are reinforced.

Patriarchs of all generations spread the Buddhadharma where it had not been heard before. I aspire to follow in their footsteps, despite all the difficulties. I vow to emulate the virtuous ones of the ancient times and establish monastic systems in lands where Buddhism is foreign, and guide those who suffer and truly benefit them with the Buddhadharma.

In the end, I wish you all fulfilment of Dharma joy and auspiciousness of six periods!