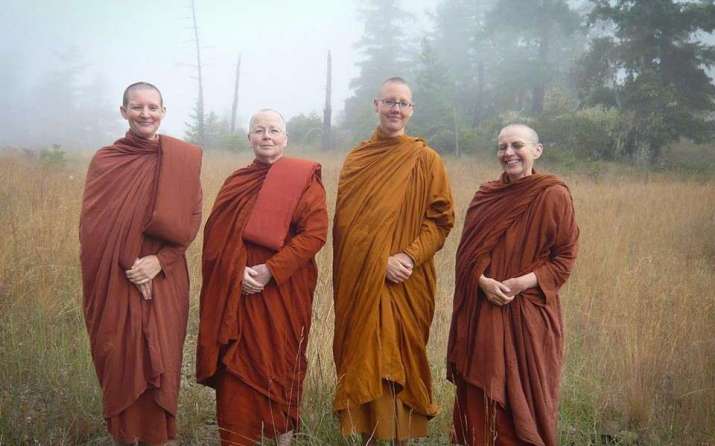

Ayya Adhimutti was ordained as a bhikkhuni in the Theravada Forest Tradition at Aranya Bodhi Hermitage in 2010. The essay below is an adaption, with her permission, from an earlier article she wrote about her ordination as a samaneri in 2008, at which time the female sangha at Santi was just finding its feet.

On 9 March 2008—almost exactly a decade ago—I went forth from my home to homelessness with my bhikkhuni teacher Ayya Tathaaloka as my upajjaya.

Under more “normal” circumstances, I would then have taken dependence on Ayya Tathaaloka and the bhikkhuni sangha for my training, but as a reflection of the times (and a reflection of his great generosity and compassion), I went across to the bhikkhu sangha and took dependence on Bhante Sujato.

Since I first ordained as a mae chee in Thailand in 2005, I’ve learned through (sometimes bitter) experience the importance of space and support—physical, psychological, and intellectual, as well as spiritual—for the holy life to be well lived.

I hope that myordination and the ordinations of others have helped to turn over a new page on our tradition (the Thai Forest Tradition) so that after this, as a woman, one will be able to go forth within a context that assumes the natural progression of samaneri status to be ordination as a bhikkhuni.

For myself, after experiencing other forms of ordination, there is a sense of rightness and flow to this progression. It feels like bones that have long been misaligned and caused so much distress are now in their natural place.

I appreciate the courage, integrity, and great beauty of the many women before me who managed to carve out a coherent monastic life as a mae chee with 10-precept ordination. I am grateful and inspired by the work they have done; the ground they have prepared; the way they have grown, in often difficult and unsupportive conditions. For myself, however, 10-precept ordination had a feeling of incompleteness.

Until recently, bhikkhuni ordination was a bit of a non-issue within the Thai Forest Tradition. There was this idea that the bhikkhuni sangha had died out 1,000 years ago and could not be revived. Therefore, women should be content with other forms of ordination—as mae chee, or 10-precept nuns—full ordination not being necessary for them. So, it was within a wider monastic context shaped by these sorts of ideas that I first came to Santi in 2007.

Back then, things were a little different. Santi had a dual sangha living there, and with great joy I had the opportunity to serve both bhikkhus and bhikkhunis. Furthermore, issues such as bhikkhuni ordination and the place and situation of women in Buddhism—issues that form the texture and rhythm of my monastic life as a woman—were actively engaged with, discussed, and debated. Outside of this small monastery, however, these issues were largely ignored and pushed aside. The image of, and loyalty to, an all-male sangha had a resilience and a strength that was almost impossible to stand up to.

In order to allow bhikkhuni ordination to take root and flourish, we needed a countercurrent to the mainstream within the river of our tradition. A special combination of skills and factors was necessary to bring this about. It was necessary to have people who had undergone training within the tradition, who understood it intimately, and who had great appreciation and faith for the beauty and gifts it has to offer. Furthermore, we needed people with enough clarity to see the weaknesses of the tradition, enough compassion to be moved by the suffering caused by the blindspots of traditional structures, and the strength, wisdom, and conviction to heal these.

When one sees the injustice of suffering caused by traditional structures—especially, in this case, those denying full ordination and participation for women in monastic life—it is necessary to look deeply into the texts to see if indeed the Buddha’s original intentions and teachings support the assumptions underlying traditional structures. And in doing this sort of work, in challenging ideas that have long been held as sacred, one inevitably faces strong opposition. So it has taken enormous strength and stamina to stand against the main currents of the river and to investigate.

Over the last decade, meditators and scholars such as Bhante Sujato, Ayya Tathaaloka, and Ven. Bhikkhu Bodhi have had the dedication, clarity, and strength to undertake this sort of investigation. By looking deeply into the traditions in which we exist, examining both the ways in which they have grown, and the assumptions that underlie them, they have been able to expose these assumptions and enabled us to see our traditions in a new light. They have allowed us to separate the original intentions of the Buddha from cultural accretions. By doing so, these monastics have created new currents within the vast river of our tradition and allowed the causes and conditions to flow that support bhikkhuni ordination.

This work had been going along steadily and quietly for a long time—largely disregarded and ignored in little side-streams and backwaters, but having no real impact on the main flow of events. In July 2007, however, there was an international conference about bhikkhuni ordination in Hamburg. Ayya Tathaaloka, Bhante Sujato, and Ven. Bhikkhu Bodhi spoke clearly and intelligently as Theravada monastics about many of the assumptions that prevent the bhikkhuni sangha from taking root and flourishing. After these ideas were voiced at an international forum of this kind, the necessity for bhikkhuni ordination was no longer able to be swept aside by mainstream assumptions, but began to be more openly recognized and engaged with within the main currents of the river.

In November 2007, Bhante Sujato had the inspiration to invite bhikkhunis, nuns with various forms of ordination, and other women to Santi to discuss issues surrounding bhikkhuni ordination. This idea was enthusiastically taken up by the community there. At Santi, although we had the vision of a flourishing bhikkhunisangha, we felt alone and unsupported as young nuns and nuns-to-be within our wider context, which has denied the existence and necessity of a bhikkhuni sangha. We were not stepping into a context and structure that was already formed and guaranteed support and respect as the monks do; but as young nuns, still feeling very tender and in need of guidance, we felt as if we were stepping into nothing, and that we had to build the bridge as we walked on it.

It was appropriate that Santi provided the space for the first such gathering within the Forest Tradition. The land that our monastery is built upon was generously provided by Ven. Nirodha, the first 10-precept Theravada nun to ordain on Australian soil. Bhante Sujato was the abbot, a monk whose conviction about the necessity of a bhikkhuni sangha stems from his compassion in seeing the suffering caused when the desire to go forth and live the monastic life in its full form is denied, and from his deep contemplation and intimate knowledge of the early Buddhist texts, which provide a clear vision of the necessity of the fourfold sangha.

Our wonderful monk brothers, Bhante Jaganatha, Bhante Mettabha, and Bhante Tapassi have supported us and are with us every step of the way. We also have the support of many lay people, both near and far, who see that the time for the flourishing of the fourfold sangha has come and who support us with their enthusiasm and energy on many levels.

Since the first publication of this article, Santi Forest Monastery, in New South Wales, Australia, has been transformed into a thriving a bhikkhuni monastery, known for its advocacy and support of full ordination for Buddhist nuns. Bhante Sujato left the monastery in 2012 and handed it over to the nun’s community to develop it into a bhikkhuni monastery, a decision supported by Santi’s spiritual director, Ajahn Brahm. Since 2014, Ayya Nirodha, who ordained as a bhikkhuni in 2009, with Ayya Tathaaloka as bhikkhuni preceptor, has been the senior bhikkhuni-in-residence at Santi. Ayya Adhimutti currently travels across Asia.

A very inspiring read, thank you for sharing. You are making known a path in NZ, other women can walk upon. I aspire to one day ordain and become a Bhikkhuni – maybe the first Maori Bhikkhuni, i dont know? Until that day, I am practising the causes and conditions that will give rise to such an event. I am glad to have fellow NZ women like yourself Ayya Adhimutti to look up to. Be well and Happy. Karamea