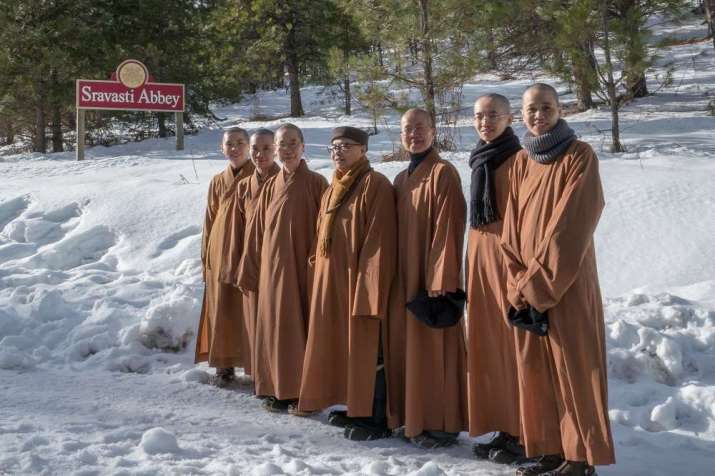

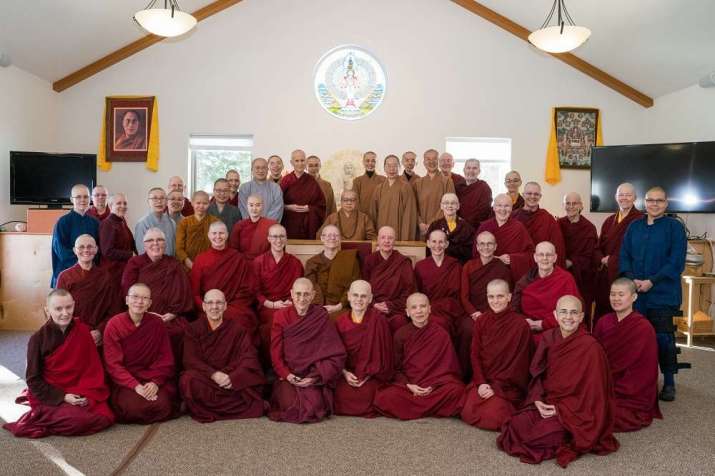

Fifty Buddhist nuns from around the world gathered at Sravasti Abbey in Newport, Washington from 22 January–8 February to receive teachings on the Dharmaguptaka Vinaya from Venerable Bhikshuni Master Wu Yin and her disciples from the Luminary International Buddhist Society (LIBS) in Taiwan. Attending at the invitation of Ven. Thubten Chodron, founder and abbess of Sravasti Abbey, the teachings were a first for Master Wu Yin and her disciples in the United States. Buddhistdoor Global columnist Harsha Menon interviewed Ven. Thubten Chodron, a humble yet formidable force in American Buddhism, about the purpose and historic nature of these teachings, and what they mean for the global bhikshuni sangha.

Buddhistdoor Global: What inspired you to invite Master Wu Yin and the Luminary Temple nuns to Sravasti Abbey?

Venerable Thubten Chodron: Back in 1989, when I was on a teaching tour in the US, I was introduced to a disciple of Master Wu Yin named Ven. Jendy, who was living at their LIBS temple in Kirkland, Washington. We became very good friends and when I was organizing a program in Bodh Gaya called “Life As a Western Buddhist Nun” in 1996, Ven. Jendy suggested we invite her teacher Ven. Wu Yin to come and teach.

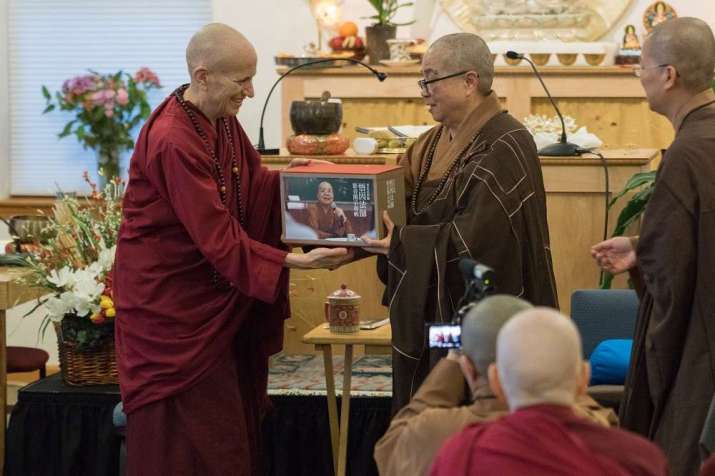

Ven. Wu Yin agreed and loved teaching the nuns. Her teachings really resonated with us, so after the program I transcribed and edited her teachings with the help of Ven. Jendy, who clarified questions with Ven. Wu Yin. Together, we produced the book Choosing Simplicity, which consists of Master Wu Yin’s teachings on the bhikshuni Pratimoksha (a text containing precepts for fully ordained Buddhist monastics).

Over the years, my relationship with Ven. Wu Yin and the Luminary nuns developed. After we found land in rural Washington for our Abbey, Ven. Jendy came to help when we started ordaining nuns. She and some other nuns translated the ordination text into English, and during the ordination ceremony I took the role of preceptor and she was the instructor, the acharya. So there has always been a close connection and collaboration between us.

In 2016, I went to Taiwan for an award ceremony for international bhikshunis. Although we had already invited Master Wu Yin to teach at the “Living Vinaya in the West” program at Sravasti Abbey at an earlier time, I invited her again and she accepted.

BDG: What did the master and her disciples teach during the program?

VTC: Put informally, the topic of Master Wu Yin’s teachings was: “What does it mean to be a nun?” and particularly, “What does it mean to become a bhikshuni [a fully ordained nun]?” She addressed the audience as if they were already bhikshunis, because in her eyes being a sramaneri [novice] is not all you can be; it’s simply a step toward becoming a bhikshuni.

Master Wu Yin spoke about women’s capabilities and emphasized that the bhikshuni and the bhikshu sanghas each handle their own affairs. She explained the mentality, lifestyle, and activities of a bhikshuni, discussing what the Buddha prescribed in the Vinaya as actions that the sangha should engage in and those that we should abandon. She also spoke extensively about how the sangha could and should benefit society. We must not withdraw from society and focus only on our meditation practice—we need to understand that both community life in the sangha and with socially engaged Buddhism also trains our minds. It is through our interaction with others that we see the effects of our meditation practice and that we are confronted with those aspects of ourselves that we need to work on.

During the event, her disciples taught the Skandhaka—a part of the Vinaya that contains 20 chapters on different topics that concern monastic life. For instance, they discussed what life as a sangha member is like, what the requirements are for ordination, and how a sangha should govern itself. This last relates to how a monastic community should govern itself, but the principles can be applied to any kind of group; it explains how a group can function in a healthy way.

BDG: What makes these teachings historic?

VTC: I think the nuns make it historic, especially Western nuns—primarily from the Tibetan Buddhist tradition, with some from the Chinese Mahayana and Theravada traditions—coming together here at Sravasti Abbey, to form a community for these days and to listen to the teachings from a widely respected female teacher. There are very few female teachers in the Tibetan and Theravada traditions, although there are many more in the Chinese Mahayana tradition. In countries where there is bhikshuni ordination, the status, the education, and other opportunities for nuns are much greater than in the countries that lack bhikshuni ordination. For some of us, this was the first time to meet an abbess who runs her own monastery, who has founded a Buddhist institute, has an international organization with seven branches, and operates a charity organization. Someone like that is an inspiring role model for people gathered here. She continually encouraged us to gain more knowledge, to preserve and spread the Buddha’s teachings, and to benefit sentient beings.

Ven. Wu Yin repeatedly told the nuns, “You people will grow in the Dharma and become teachers in the future.” She explained that to become a teacher, to become a preceptor, you have to study and learn. Knowledge and wisdom are very important: when you train yourselves well, in the future you can become leaders in the Buddhist community, especially in the bhikshuni sangha.

Half the world’s population are female, and women much prefer to talk to other women when they have difficulties, need counseling, and so on, so Ven. Wu Yin said, “Think about what you can do with your life, and go for it. Don’t put yourselves down, but think big.”

During the teachings, people heard this message every day and saw how she interacted with her students. They saw the way her students conduct themselves, the way they cooperate and function as a whole. It gave the Western nuns an example of what they can do, of what they can become.

BDG: How do you see the future of the global bhikshuni sangha, and how does a strong bhikshuni sangha help Buddhism?

VTC: Bhikshunis and nuns coming together and supporting each other is very helpful for their individual practice and for the communities to which they belong. For example, everybody at the program has been enriched and will take what they’ve learned back home to their own communities to share.

I think that Buddhism in the West is not going to spread unless women are involved and gender discrimination is abandoned. I’m not saying this because I’m a woman; many men in the West have said this to me. They want to hear Dharma teachings from women too. If the old stereotypes about women remain, and women do not have equal opportunities and lack self confidence, Buddhism will not flourish in this country. For the long-term spread and flowering of the Dharma in the West, this kind of program is very important because it empowers women and gives them the knowledge and skills to be a force that can help society, and help to preserve and spread the Dharma.

Another reason why this teaching is historic is that Buddhism in the West has mostly become a lay movement, with very few monastic sanghas. Historically, the role of the monastic sangha has been to preserve the Buddha’s teachings and pass them down to future generations, but in America, monastics are often perceived as strange people—men in skirts and women with shaved heads. They are celibate and don’t have their own families—how strange!

Some American Buddhists think, “We lay practitioners are going to modernize Buddhism, we are going to remove the mythology, take out the hierarchy between monastics and lay people, and do away with patriarchy. We are moder, advanced thinkers.”

When they look at the monastic sangha, they see hierarchy, and when they look at the nuns, they see patriarchy. While I and other nuns are not supporters of rigid hierarchy or patriarchy, we don’t want to throw the Buddha out with the bath water, so to speak. For example, I am not equal to my teachers; I respect them and want to be able to show that respect. I want to be guided by their wisdom.

In America in general, there is little understanding of why someone would choose to be celibate and choose not to have a family. While we monastics see giving up the household as creating good conditions for a spiritual practice, most people do not. So, unfortunately, we find that there is an attitude among lay Dharma practitioners—and even lay Buddhist teachers—of “people who are celibate are negating their sexual side, they are avoiding intimate relationships and the commitment and emotional trials of intimate relationships. Becoming a monastic is a way of escaping reality. We practice in society, we have families, we drink, we live like everybody else so we can spread the Dharma because we don’t have this kind of hierarchy or wear strange clothes.”

I am generalizing here and I don’t want to offend anybody, but I have encountered these attitudes numerous times. When people express these thoughts, I think, “Oh, if only changing clothes and cutting your hair made it that easy to escape from problems! Unfortunately, our ignorance, anger, and attachment all come with us into the monastery, where we can’t escape from them! The only thing to do is to practice the Dharma to overcome our afflictions.”

So when the nuns gathered together for the “Living Vinaya in the West” programt, there was immediate recognition of each other’s aims in life. We didn’t need to explain why we were ordained, why we choose to be celibate and have a simple lifestyle dedicated to spiritual study and practice. We understood each other’s values and priorities instantly because we share those same values and priorities.

In short, “Living Vinaya in the West” has empowered the monastic sangha and the nuns in particular, and will have long-term beneficial effects for all beings. As we study more and our knowledge deepens, we have more self-confidence regarding training our own minds through our Dharma practice and helping other to learn the Buddha’s remarkable and liberating teachings. By means of the ripple effect, this will have a long-lasting, positive impact.

See more

Sravasti Abbey

Bhikshuni Thubten Chodron

Luminary International Buddhist Society